References Zettelkasten Memex People Tiago Forte Niklas Luhmann Vannevar Bush

What is the Second Brain

A Second Brain is a personal knowledge system that helps you capture, organize, and reuse information outside your head.

Instead of relying on memory, you store useful ideas, notes, and resources in a structured digital space so you can:

- Think more clearly

- Learn faster

- Make better decisions

- Create higher-quality work

Your biological brain focuses on thinking and problem-solving.

Your second brain handles storage and retrieval.

Why it matters

In a world of constant information, the ability to retain and apply knowledge is more valuable than just consuming it.

A Second Brain turns information into usable insight.

The Cognitive Extension: A Comprehensive Analysis of the Second Brain Ecosystem in the Age of Artificial Intelligence

Part I: The Genesis and Evolution of Externalized Cognition

The pursuit of augmenting human intelligence through external systems is not a novel phenomenon born of the digital age; it is a fundamental aspect of the human condition, a trajectory that stretches from the clay tablets of Mesopotamia to the vector databases of modern artificial intelligence. The concept of the “Second Brain”—a term popularized in the 21st century to describe a methodology for saving and systematically reminding oneself of the ideas, inspirations, insights, and connections gained through experience—is the latest iteration of this ancestral drive to overcome the biological limitations of memory.1

This report explores the depth of the Second Brain concept, tracing its lineage from the ink-stained pages of Renaissance commonplace books to the generative neural networks of 2026. It serves as a definitive guide for knowledge workers, executives, and researchers seeking to navigate the transition from manual organization to AI-augmented cognition.

1.1 The Pre-Digital Ancestry: From Commonplace Books to Zettelkasten

Long before the advent of the microprocessor, intellectuals and natural philosophers recognized the fragility of the human mind. The biological brain is an unparalleled pattern-matching engine, but it is a notoriously unreliable storage medium. Memories fade, details blur, and the context of an insight is often lost within moments of its conception. To combat this entropy, thinkers developed external substrates to anchor their cognition.

The Commonplace Book: The Renaissance Repository

The Commonplace Book, emerging prominently during the Renaissance and Enlightenment, serves as the spiritual progenitor of the modern Second Brain. Figures such as John Locke, Leonardo da Vinci, and Virginia Woolf utilized these volumes not merely as diaries, but as repositories for recipes, quotes, scientific observations, and theological arguments.1 The practice was grounded in the Latin concept of locus communis—a “common place” where ideas could be gathered.

Unlike a journal, which is chronological and introspective, a commonplace book was functional and external. It was a tool for “thinking with.” A naturalist might transcribe a description of a botanical specimen on one page and a recipe for ink on the next. The value lay in the act of transcription itself, which served as a forcing function for attention. However, the limitation of the commonplace book lay in its linearity; once a page was filled, the information was static, bound by the physical sequence of entry. Retrieving a specific idea required remembering where in the volume it was written, or maintaining a cumbersome manual index.3

The Zettelkasten Method: Atomicity and Conversation

A significant evolutionary leap occurred with the development of the Zettelkasten (slip-box) method, most famously refined by the German sociologist Niklas Luhmann.1 Luhmann, a prolific scholar who published over 70 books and 400 scholarly articles, attributed his productivity not to his own genius, but to his partnership with his slip-box.5

Luhmann’s system was revolutionary because it introduced two critical concepts to knowledge management: atomicity and connectivity.

-

Atomicity: Unlike the bound pages of a commonplace book, Luhmann’s notes were written on individual index cards, each containing a single, distinct idea. This atomicity meant that ideas could be rearranged, discarded, or connected in infinite configurations.5

-

Connectivity: Luhmann assigned each card a unique alphanumeric identifier (e.g., 21/3d7). This allowed him to link cards together, branching off into sub-topics and tangential thoughts. A card about “System Theory” could branch into “Biological Systems,” which could further branch into “Autopoiesis.”

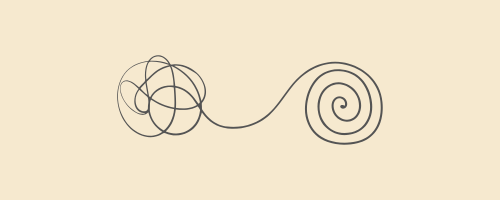

The genius of the Zettelkasten lay not in storage, but in retrieval and conversation. Luhmann described his slip-box as a “communication partner”—a system that could surprise him.4 By manually linking cards through references, he created a web of thought that mimicked the associative nature of the human brain. When he queried the box for a topic, the internal links would lead him down unexpected paths, effectively allowing the system to “speak back” to him. This manual linking process transformed the archive from a graveyard of facts into a generator of new theories. The Zettelkasten method demonstrated that externalized knowledge becomes valuable only when it is networked, allowing for the emergence of “smart notes” that are greater than the sum of their parts.5

1.2 The Digital Dawn: Vannevar Bush and the Memex

As the sheer volume of human knowledge expanded exponentially in the 20th century, the need for mechanical aid became apparent. The industrial production of scientific literature meant that no single individual could keep abreast of their field, let alone adjacent disciplines. In his seminal 1945 essay _As We May Think, Vannevar Bush articulated this problem with prescient clarity.8

Bush criticized the indexing systems of libraries, which organized data alphabetically or numerically—structures that are fundamentally alien to the human mind’s associative operation. “The human mind does not work that way,” Bush wrote. “It operates by association. With one item in its grasp, it snaps instantly to the next that is suggested by the association of ideas”.10

The Memex Vision

Bush proposed the Memex (memory extender), a hypothetical electromechanical device that would allow an individual to store all their books, records, and communications. Crucially, the Memex would allow users to create “associative trails” running through the material.8 A user could link a book on history to a letter from a colleague, creating a permanent path that could be recalled instantly.

Bush envisioned a new profession of “trail blazers”—individuals who would navigate the vast record and establish useful paths for others.11 Although the Memex was never built, its conceptual framework—specifically the idea of associative linking—laid the groundwork for hypertext, the World Wide Web, and modern Personal Knowledge Management (PKM) tools.9 The Memex was the first clear articulation of the Second Brain as a technological necessity, bridging the gap between the static library and the dynamic mind.

1.3 The Formalization of the “Second Brain”

In the early 21st century, the proliferation of cloud computing and mobile devices created a paradox: information was universally accessible, yet personal retention and synthesis were declining. We entered the era of “Information Overload,” where the friction of capturing information dropped to zero, but the friction of utilizing it skyrocketed. Into this gap stepped Tiago Forte, who formalized the “Building a Second Brain” (BASB) methodology.2

Forte’s contribution was to shift the focus from knowledge accumulation to actionability. While the Zettelkasten focused on generating academic insights over a lifetime, the Second Brain methodology was designed for the modern knowledge worker drowning in emails, Slack messages, and project deadlines. It introduced a shift from organizing by topic (e.g., “Marketing,” “Psychology”) to organizing by project and outcome.7

This philosophy fundamentally altered the landscape of productivity, moving the goalpost from “having information” to “connecting and expressing information.” It argues that we must treat our digital repositories not as storage units, but as production studios. The Second Brain is defined as a system outside your physical body that allows you to preserve your best thinking, ensuring that no insight is ever lost and that every project stands on the shoulders of your past work.2

Part II: Theoretical Frameworks and Methodology

To transition from a chaotic collection of digital artifacts to a functioning Second Brain, practitioners rely on structured methodologies. These frameworks serve as the operating system for personal knowledge, ensuring that the intake of information leads to tangible output rather than digital hoarding.

2.1 The PARA Method: Organizing for Actionability

One of the most persistent challenges in knowledge management is the question of where to put a new piece of information. Traditional systems rely on topical categorization (e.g., “Files > Marketing > Assets”), but this breaks down when a file relates to multiple topics or changes relevance over time. The PARA Method solves this by organizing information based on its actionability horizon rather than its subject matter.12

| Category | Definition | Actionability Horizon | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Projects | Short-term efforts with a defined goal and deadline. | Immediate / High | ”Q3 Sales Report,” “Website Redesign,” “Trip to Japan” |

| Areas | Long-term responsibilities with no deadline but requiring maintenance. | Ongoing / Medium | ”Health,” “Finances,” “Professional Development,” “Hiring” |

| Resources | Topics of ongoing interest that may be useful in the future. | Potential / Low | ”Web Design Trends,” “Coffee Brewing,” “Leadership Theory” |

| Archives | Inactive items from the other three categories. | Historic / None | ”Completed Q3 Report,” “Old Health Records,” “Defunct Project X” |

Table 1: The PARA Organizational Framework 7

The Dynamic Flow of Information

The power of PARA lies in its fluidity. A single piece of information—for example, a PDF on “SEO Best Practices”—can travel through all four categories during its lifecycle:

-

Resource: Initially, it is saved in “Resources > SEO” because the user finds it interesting.

-

Project: When the user starts a project “Launch Blog,” they move the PDF to “Projects > Launch Blog” to make it immediately accessible.

-

Archive: Once the blog is launched, the project folder (containing the PDF) is moved to “Archives.”

This dynamic movement prevents the “siloing” of information. It ensures that the user’s digital environment always reflects their current priorities, reducing the cognitive load required to find relevant materials.7

2.2 The CODE Framework: The Lifecycle of Knowledge

While PARA handles organization, the CODE Framework (Capture, Organize, Distill, Express) defines the workflow—how information moves from the external world into the Second Brain and back out as creative work.12

1. Capture: Keeping What Resonates

The first step is identifying and preserving information that triggers a reaction—what Forte calls “resonance”.16 In an age of algorithmic feeds, the skill of filtering is more critical than the skill of finding.

-

The 12 Favorite Problems: A recommended practice to guide capture is to maintain a list of open questions or “favorite problems” (e.g., “How can we democratize education?” or “How do I balance work and health?”). Information is captured only if it relates to one of these active inquiries, preventing the accumulation of random trivia.13

-

Tools: Capture must be frictionless. Tools like Readwise, web clippers, and voice memos are essential to ensure that the moment of insight is not lost to the friction of the interface.17

2. Organize: Actionability over Subject

As detailed in the PARA section, organization is strictly utilitarian. The goal is not to build a library for the sake of completeness, but to stage information for future projects. The mantra is: “Organize for action, not for storage”.13

3. Distill: Finding the Essence

Capturing a 5,000-word article is useless if one must re-read the entire text to retrieve the insight. Distillation involves Progressive Summarization—a technique of layering highlights to compress information without losing context.13

-

Layer 1: Save the full text.

-

Layer 2: Bold the key passages.

-

Layer 3: Highlight the “best of the best” within the bolded sections.

-

Layer 4: Write an executive summary at the top of the note in your own words.

This process respects the “future self.” By compressing the information now, the user reduces the cognitive load required to utilize the note later. It turns “reading” into “processing”.13

4. Express: Showing Your Work

The ultimate purpose of a Second Brain is output. “Expression” involves assembling the distilled notes into new creative works—articles, proposals, products, or decisions.13 This aligns with the “Remix” culture of creativity; no idea is created in a vacuum, but is rather a recombination of existing parts (kitbashing).15

2.3 The Collector’s Fallacy: The Enemy of Insight

A pervasive pitfall in PKM is the Collector’s Fallacy—the false belief that “to know about something” is the same as “knowing it”.21 Digital tools make collecting incredibly easy; clicking “save to Notion” provides a dopamine hit similar to actually learning the material.22

-

Symptoms: Users amass thousands of bookmarks, PDFs, and “read later” articles that are never revisited. The system becomes a “mausoleum” of good intentions.22

-

The Zettelkasten Antidote: The Zettelkasten method counters this by requiring elaboration. You cannot simply save a link; you must write a new note linking it to an existing idea. This friction is intentional (“eufriction”) and forces cognitive engagement.5

-

AI’s Role: Generative AI risks worsening this fallacy by allowing users to auto-summarize everything without reading it. Conversely, AI agents can potentially “resurface” forgotten notes, forcing the user to confront their collection.22

2.4 Knowledge Archetypes: Architects, Gardeners, and Librarians

Different personalities gravitate toward different structural metaphors for their Second Brain. Understanding one’s archetype is crucial for selecting the right tools and workflows.24

| Archetype | Philosophy | Preferred Tools | Structural Metaphor |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Architect | Loves structure, hierarchy, and systems. Wants to design a perfect framework upfront. | Notion, Coda, Tana | The Building (Blueprints first) |

| The Gardener | Prefers organic growth. Notes are “seeds” that grow connections over time. Values serendipity. | Obsidian, Roam, Logseq | The Garden (Plant and water) |

| The Librarian | Focused on retrieval and cataloging. Wants a place for everything. Often research-focused. | Evernote, DevonThink, Bear | The Warehouse (Dewey Decimal) |

| The Student | Short-term focus, optimizing for specific outputs (exams, papers). Needs speed and simplicity. | Apple Notes, Google Keep | The Binder (Subject-based) |

Table 2: The Four Archetypes of Knowledge Management Personalities 24

The friction often arises when a “Gardener” tries to use an “Architect” tool (e.g., trying to force rigid databases into Obsidian) or vice versa. The most successful Second Brains align the tool’s affordances with the user’s cognitive style.26

Part III: The AI Inflection Point (2024-2026)

The integration of Artificial Intelligence into Personal Knowledge Management marks the most significant shift since the transition from paper to digital. We are moving from Passive Storage (where data sits until retrieved) to Active Curation (where the system proactively surfaces connections).

3.1 From Taxonomy to Semantic Resonance

For decades, digital organization relied on Taxonomy: the manual categorization of items into folders and tags. This system is fragile; if a user misfiles a document or forgets the specific keyword, the information is lost.

The Mechanics of Semantic Search

Modern AI-driven PKM tools utilize Vector Embeddings. They convert text into numerical vectors that represent meaning rather than just characters. This allows for “Semantic Search”—querying the system based on concepts.27

-

Example: A user searches for “How to motivate a team.” A traditional keyword search might miss a note titled “Lessons from Shackleton’s Antarctic Expedition” because it lacks the word “motivate.” A semantic search engine understands that “Shackleton” and “leadership” are semantically related to “team motivation” and surfaces the note.30

-

The Death of Folders?: Some theorists argue that sufficiently advanced semantic search renders folders obsolete.31 If the system can always find the right document based on intent, the manual labor of filing becomes redundancy (what is effectively “digital manual labor”). However, many users still find psychological comfort in the visual structure of folders (the “Architect” archetype).32

3.2 Generative Curation and the “Active” Second Brain

Traditional Second Brains are passive; they only reflect what the user puts in. AI-Native tools like Mem, NotebookLM, and Saner.ai act as active partners.

Auto-Tagging and Linking

Tools like Mem use AI to scan the content of a new note and automatically suggest tags or link it to related notes from the past.23 This mimics the Zettelkasten’s “associative trails” but automates the labor-intensive linking process. This creates a “self-organizing” workspace where the relationship between data points is maintained by the machine.34

Contextual Resurfacing

Instead of waiting for a search query, AI tools can surface relevant notes proactively. For instance, while a user writes a document about “Climate Change,” the side-panel might automatically display notes taken three years ago on “Renewable Energy Economics”.23 This transforms the Second Brain from a repository into a “Feed of Relevance,” ensuring that past work is constantly recycled into current projects.

Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG)

RAG allows users to “chat” with their Second Brain. Instead of retrieving a list of documents, the AI reads the relevant notes and synthesizes an answer.36

- Case Study: NotebookLM: Google’s NotebookLM grounds its AI strictly in the documents uploaded by the user. It creates a “closed loop” reliable ecosystem. A user can upload 50 PDF research papers and ask, “What is the consensus on variable reinforcement schedules?” The AI answers with citations mapping directly to the source text, virtually eliminating hallucinations common in open-ended LLMs.36

3.3 The Shift from Librarian to Curator

As AI takes over the “Librarian” functions (cataloging, tagging, retrieving), the human role shifts to that of a Strategic Curator.38

-

The New Responsibility: The user’s value is no longer in organizing the information, but in selecting the input and verifying the output. The “Curator” decides what enters the system (filtering high-quality data) and shapes the “training data” of their personal AI.40

-

Ethical Curation: In the context of libraries and corporate knowledge bases, this involves ensuring that the AI is trained on diverse and accurate data, avoiding bias that might be inherent in a raw data dump.39

-

Metadata Engineering: Librarians and advanced users are now becoming “metadata engineers,” ensuring that data is structured in a way that maximizes the AI’s ability to understand it.39

3.4 Privacy, Ethics, and the “Black Box” Problem

The outsourcing of memory to AI raises profound privacy concerns. To offer semantic search and auto-tagging, cloud-based AI tools must ingest and index the user’s private thoughts, journals, and proprietary business data.41

Data Leakage and Sovereignty

There is a legitimate fear that personal data could be used to train future public models, potentially exposing sensitive secrets (the “Samsung ChatGPT leak” scenario).42 “When data is procured for AI development without the express consent or knowledge of the people from whom it’s being collected,” privacy risks escalate.41

The Local LLM Movement

A growing subculture of privacy-focused users (“Local-First” advocates) rejects cloud AI in favor of running Open Source LLMs (like Llama 3 or Mistral) locally on their own hardware.43

-

Workflow: Using tools like Ollama or GPT4All, users create a localized “chat with your docs” experience where no data ever leaves their machine. This aligns with the philosophy of tools like Obsidian, which prioritize local markdown files over proprietary cloud databases.44

-

Trade-off: Local AI often lacks the sheer reasoning power and convenience of massive cloud models like GPT-4, requiring users to balance privacy against capability.43

3.5 The Infinite Context Window

The technical constraint of “context windows” (how much information an AI can hold in working memory) is vanishing. Models like Gemini 1.5 Pro now support context windows of over 1-2 million tokens (equivalent to dozens of books).46

-

Implication: Soon, a user will not need to “organize” or “chunk” data for the AI. They could theoretically feed their entire digital life (every email, note, and document from the last decade) into the context window.

-

The “Chat with Your Life” Interface: The primary interface for the Second Brain will likely shift from a file explorer to a chat interface. The user will ask, “What were my main concerns about Project Alpha in 2023?” and the system will synthesize the answer from the raw data stream, rendering manual tagging obsolete.47

Part IV: The Tooling Landscape (2025-2026)

The market for Second Brain tools has fractured into distinct categories, each serving different philosophies and AI readiness levels. This section provides a comparative analysis to guide selection.

4.1 The Networked Thought Leaders (The Gardeners)

-

Obsidian: The gold standard for “local-first” PKM. It uses plain text Markdown files stored on the user’s device.35

-

AI Integration: Not native, but achieved through community plugins (e.g., Smart Connections, Copilot). This allows users to choose their AI provider (OpenAI, Claude, or Local LLM).45

-

Best For: Academics, researchers, and privacy advocates who want a “forever” archive that doesn’t depend on a startup’s survival.

-

-

Roam Research / Logseq: Pioneers of bi-directional linking. Logseq offers a similar local-first privacy model to Obsidian but with an outliner (bullet-point) focus.50

4.2 The All-in-One Workspaces (The Architects)

-

Notion: The dominant player for project management and team wikis.

-

AI Integration: Notion AI is deeply integrated. It can summarize database rows, auto-fill properties, and generate text within the block editor.49

-

Best For: Managers, startups, and students who need to blend “doing” (tasks) with “thinking” (notes).52

-

-

Coda: Similar to Notion but with stronger automation and formula capabilities, acting almost as an app-builder.

4.3 The AI-Native Systems (The Self-Organizing)

-

Mem.ai: A “self-organizing” workspace. It eschews folders entirely, relying on AI to tag and surface notes. It learns the user’s writing style and people network.23

- Best For: Chaotic thinkers and fast-paced executives who hate filing and want a “magic assistant.”

-

NotebookLM (Google): A research powerhouse. It focuses on “grounding” AI in specific sources.

- Unique Feature: Audio Overviews. It can convert a set of dry research papers into an engaging “podcast” where two AI hosts discuss the material, helping auditory learners synthesize information.36

-

Recall / Rewind: The “Time Machine” approach. These tools record screen history and meeting audio.

-

Recall (Microsoft): Integrated into Windows, taking snapshots of activity for semantic retrieval. (Controversial due to privacy).53

-

Rewind.ai (Mac): Records everything seen, said, or heard, compressing it locally. It allows users to ask, “What was that tweet I saw last week about crypto?” and finds it via OCR.53

-

4.4 Comparative Analysis of Leading Tools

| Feature | Obsidian | Notion | Mem.ai | NotebookLM | Rewind.ai |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Philosophy | Gardener (Networked) | Architect (Structured) | Flow (Self-Organizing) | Researcher (Grounded) | Time Machine (Record) |

| Storage Location | Local Files (Markdown) | Cloud (Proprietary) | Cloud (Proprietary) | Cloud (Google) | Local (Mac Optimized) |

| AI Capabilities | Via Plugins (Flexible) | Native (Generative & DB) | Native (Auto-tag/Link) | Native (RAG/Audio) | Native (OCR/ASR) |

| Privacy | High (User controlled) | Medium (Enterprise enc.) | Low (AI training likely) | Medium (Google policies) | High (Local only) |

| Learning Curve | High (Tinkerer friendly) | Medium (Template based) | Low (Just write) | Low (Upload & Chat) | Low (Install & Forget) |

| Best Use Case | Deep Research / Writing | Team Projects / Wikis | Daily Logs / Brain Dump | Study / Synthesis | Recovering lost context |

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of Key Second Brain Tools in 2026 35

Part V: Applied Architectures and Case Studies

The implementation of a Second Brain varies drastically across professions. A “one size fits all” approach fails because the input streams and desired outputs differ for a student versus a CEO. Below are detailed walkthroughs of how specific personas implement these systems in the real world.

Case Study 1: The Academic Researcher (Obsidian & Zotero)

Persona: A PhD candidate in Sociology writing a thesis.

Goal: To manage 500+ citations and generate original insights without plagiarism.

Tool Stack: Zotero (Capture), Obsidian (Distill/Connect), Readwise (Sync).

The Workflow:

-

Capture Phase: The researcher reads a PDF in Zotero (citation manager). They highlight key passages regarding “urban isolation.” Zotero automatically extracts metadata (author, year, publication).56

-

Syncing: A plugin (e.g., Zotero Integration) pulls the highlights into Obsidian. Each paper gets its own “Literature Note.” The highlights are not just pasted; they are formatted with “admonition” blocks for readability.

-

Processing (The Atomic Note): The researcher does not just leave the highlights. They review them and create Atomic Notes (Zettels) for unique concepts.

-

Example: A highlight about “urban isolation” leads to a new note named

[[Urban Isolation leads to political polarization]]. -

This note is linked to other concepts like

]and]. This step requires the researcher to rewrite the idea in their own words, ensuring comprehension.

-

-

Synthesis: When writing the thesis, the researcher opens a “Canvas” in Obsidian. They drag-and-drop these atomic notes onto a visual board, rearranging them to form a linear argument.

-

Drafting: The draft is written in Obsidian using the linked notes as evidence. Citations are linked back to Zotero for the final bibliography.

Outcome: The thesis is not written from scratch but “assembled” from years of processed thought. The “blank page syndrome” is eliminated because the arguments were already developed during the note-taking phase.48

Case Study 2: The Product Manager (Notion & PARA)

Persona: A Senior PM at a tech startup managing a remote team.

Goal: To align team execution, track deliverables, and maintain a “single source of truth.”

Tool Stack: Notion (Central Hub), Slack (Communication), Loom (Video updates).

The Workflow:

-

Dashboarding: The PM starts the day on a “Command Center” page in Notion. This page aggregates databases using filtered views.57

-

View 1: “Active Projects” (from the Projects database) filtered by “Status = In Progress.”

-

View 2: “My Tasks - Due Today” (from the Master Task database).

-

View 3: “Meeting Notes - This Week.”

-

-

Capture & Organize: During a stakeholder meeting, the PM types notes directly into a new database entry linked to the “Project Alpha” page.

- AI Augmentation: After the meeting, they click “Notion AI - Summarize & Extract Action Items.” The AI generates a checklist of tasks from the messy notes and tags the relevant team members.49

-

The PARA Structure:

-

Projects: “Launch Mobile App v2.0.” All specs, designs, and tasks live here.

-

Areas: “Q3 Hiring,” “User Research,” “Team Morale.”

-

Resources: “Competitor Analysis,” “Design System Guidelines,” “SQL Snippets.”

-

-

Distillation for Team: The PM uses the “Distill” principle to create a weekly update. They review the completed tasks in the “Projects” database and write a brief narrative for the leadership team.

Outcome: The Second Brain serves not just the individual, but the team. It reduces “shoulder tapping” for information because everything is searchable and linked. The “Command Center” ensures that the PM is always reactive to the most urgent needs while keeping long-term goals visible.58

Case Study 3: The Creative Writer (Mem & Voice Capture)

Persona: A freelance fiction writer and columnist.

Goal: To capture fleeting inspiration and organize character arcs without breaking flow.

Tool Stack: Mem.ai (Knowledge Base), Otter.ai (transcription), Scrivener (Final Draft).

The Workflow:

-

Frictionless Capture: The writer is walking the dog and has an idea for a dialogue. They use Mem.ai on their phone to record a voice note. Mem transcribes it and, crucially, tags it automatically based on content (e.g.,

#dialogue,#Character:Sarah).23 -

Serendipity: When they sit down to write Chapter 4, they open Mem. As they type “Sarah enters the room,” Mem’s “Mem X” sidebar surfaces the voice note from three weeks ago, plus a snippet from an article about “Victorian interior design” they saved last year.

-

The “Gardener” Approach: Unlike the PM, the writer doesn’t use rigid folders. They rely on the stream of notes. They use “Smart Search” to ask, “What details do I have about Sarah’s childhood?” Mem retrieves relevant snippets even if the exact keywords don’t match.34

-

Refinement: The writer creates a “character bible” in Mem, linking every scene where Sarah appears. This ensures consistency in voice and behavior across the novel.

Outcome: The writer stays in the “flow state.” The administrative burden of organizing is offloaded to the AI, allowing the creative brain to focus on narrative. The system provides “surprise” connections that enrich the plot.60

Case Study 4: The Software Engineer (Local Knowledge Base)

Persona: A Senior Backend Developer.

Goal: To manage code snippets, environment configs, and troubleshooting logs without leaving the keyboard or leaking IP.

Tool Stack: Obsidian (Notes), SnippetStore (Code), Ollama (Local AI).

The Workflow:

-

Snippet Management: The engineer uses SnippetStore or a private GitHub repository for code snippets. They avoid proprietary cloud tools for code to prevent IP leakage.62

-

Troubleshooting Logs (The “Lab Notebook”): When debugging a complex issue, they open a daily note in Obsidian (or Logseq).

-

They log: “Attempt 1: Changed config X. Result: Error 500.”

-

They link: “See

[[Error 500]]regarding the load balancer.” -

This creates a historical record of “why” decisions were made, not just “what.”

-

-

Local AI Assistant: The engineer runs Ollama locally with a specialized coding model (e.g., DeepSeek Coder). They pipe their documentation into it.

-

Query: “Based on my

deployment.mdnote, what is the command to restart the staging cluster?” -

Result: The local AI retrieves the specific command from the secure notes without the data ever leaving the laptop.45

Outcome: A secure, high-speed knowledge base that integrates with the terminal and IDE, minimizing context switching and ensuring that the same bug never needs to be “solved” twice.

-

Case Study 5: The Chief of Staff (Executive Decision Support)

Persona: Chief of Staff to a CEO at a Series B company.

Goal: To synthesize information from all departments and prepare decision memos.

Tool Stack: Notion (Team), Superhuman (Email), Roam Research (Private thinking).

The Workflow:

-

Information Aggregation: The CoS receives updates from Sales, Engineering, and Marketing. They forward key emails to Roam Research (or a private Notion page).

-

Connecting the Dots: In Roam, they notice that the “Engineering delay” note links to the “Sales target miss” note. They create a new insight: “Sales missed because feature X is delayed.”

-

The Brief: They draft a “Decision Memo” for the CEO. They pull data from the disparate sources into a single view.

-

Local AI for Privacy: Dealing with sensitive financial data, they use a local LLM to summarize the quarterly board meeting transcripts, ensuring no insider information hits the public cloud.45

Outcome: The CoS acts as the “router” of the organization. Their Second Brain is the “central nervous system” that connects the isolated limbs of the company, enabling faster and more accurate executive decisions.63

Part VI: Future Horizons and the Symbiosis of Mind

As we look toward the latter half of the 2020s, the concept of the Second Brain is undergoing a radical transformation. We are moving away from the era of Storage (1990-2010) and Management (2010-2023) into the era of Synthesis (2024+).

6.1 The Rise of Autonomous Knowledge Agents

We are approaching the age of Agentic AI. Future Second Brains will not just answer questions; they will perform tasks.

-

Scenario: An autonomous agent monitors a user’s “Resources” folder. It notices the user is collecting articles about “Japanese Woodworking.” The agent proactively finds a local workshop, checks the user’s calendar, and drafts a registration email, placing it in the “Inbox” for approval.64

-

The “Digital Twin”: Eventually, the Second Brain becomes a digital twin—a model of the user’s preferences, knowledge, and history that can act as a proxy in low-stakes interactions. It could answer routine emails in the user’s voice or schedule meetings based on implicit preferences.66

6.2 The Cognitive Centaur

The evolution of the Second Brain reveals a consistent trend: the gradual offloading of lower-order cognitive functions to external substrates. First, we offloaded storage (writing), then indexing (search), and now synthesis (Generative AI).

This does not make the biological brain obsolete. Instead, it elevates the human to a higher order of cognition. When the Second Brain handles the “what” (facts) and the “where” (retrieval), the First Brain is free to focus on the “why” (meaning) and the “what if” (imagination). The most effective individuals of the coming decade will be “Cognitive Centaurs”—hybrids who seamlessly integrate their biological intuition with the vast, recall-perfect, and synthetically creative capabilities of their digital extensions.

The danger lies not in the tool, but in the passivity of the user. The “Collector’s Fallacy” remains the great filter. Those who treat AI as a dump truck for information will drown in noise; those who treat it as a partner in a dialogue—a modern Zettelkasten with a voice—will find their cognitive capacity expanded beyond biological limits. The Second Brain is no longer just a storage locker; it is becoming a mind in its own right, waiting for instructions.